Already a member? Sign in below

Advertising gimmicks are ten a penny, with attention-grabbing schemes deployed and abandoned as soon as they’ve received enough attention from the media. In February this year, though, soft drinks giant PepsiCo announced plans to advertise in a new completely new format – in space.

The partnership with Russian start-up StartRocket would have seen a cluster of cubesats (effectively a miniaturised commercial satellite) deployed to form an ‘orbital billboard’. At the time of the announcement PepsiCo’s spokeswoman Olga Mangova wrote “We believe in StartRocket potential. Orbital billboards are the revolution on the market of communications” in an email seen by Futurism.

However, last week PepsiCo confirmed that plans had been shelved, telling space.com that StartRocket had performed a single, exploratory test of the technology and that there are no current plans to roll out a fleet of space-borne billboards.

For some, that news will come as a relief. The commercialisation of space in any form, whether that’s asteroid-stripping or establishing hotels on the moon, is contentious. This particular scheme has received criticism for potentially adding to the vast amount of ‘space junk’ that is already orbiting the earth.

The reality, however, is that the commercialisation of space is coming, and has been around as an idea in science fiction for decades. Fredric Brown’s 1945 short story, ‘Pi in the Sky’, for instance, has an inventor rearranging the positions of the stars to form an advertising slogan, while Heinlein’s 1951 novella ‘The Man Who Sold The Moon’ was already trading on people’s reticence to commercialise space by having an industrialist take money to not plaster ads all over the moon.

Other satirical works of fiction, from Futurama to the short stories of Stanislaw Lem, play up the juxtaposition between the boundless potential of space and tawdry advertising of familiar products for laughs. In a typically prescient episode, Futurama featured an ad for the soft drink Slurm (“It’s highly addictive!”) projected on the ring of a planet.

Advertising is an integral part of people’s lives, so it’s only natural that we see it in so many disparate depictions of the future. Blade Runner’s dystopian future envisions towering holographic advertisements, Frederik Pohl’s novel ‘The Space Merchants’ is an environmental fable about the dangers of overconsumption that has advertising as a huge focus, and even the relatively benign future of Tad Williams’ Otherland series has characters interact with seemingly sapient advertisements.

In fact, advertising as a background detail is notable for its absence in much science fiction. In the Star Trek franchise, for instance, advertising is almost never referred to, with its most visible appearance being in Deep Space 9 in which the aggressively capitalist Quark (a member of the mercantile Ferengi race) hacks the space station to display ads for his bar in a subplot.

But while some of that technology is still beyond our reach or unfeasible from a cost perspective, much of the future of advertising has already arrived:

The last few years have seen technology companies like Google, Sony and Facebook try to create a viable market for virtual reality. Facebook bought Oculus VR for $3 billion in 2014, making a significant bet that VR is the future of media. And while the technology has been subject to Amara’s Law more than most, Sony has sold over 4 million headsets for its PlayStation VR and has plans to support the current hardware into the next console generation. It will be a while before VR is mainstream, primarily due to the high cost of the current crop of hardware, but it is undoubtedly on its way.

Naturally, a few format requires new forms of advertising. As has been noted, 30-second long interruptive adverts in any form would be especially jarring in virtual reality, which relies on total immersion for the user.

Advertising in virtual reality, then, is currently mostly relegated to having an entire program act as the ad. Ahead of the release of Spider-Man: Homecoming, for instance, Sony released the Spider-Man: Homecoming – Virtual Reality Experience on PSVR, putting the player in the shoes (and web gauntlets) of Spidey.

The recently-released DLC pack for VR rhythm game Beat Sabre has the logo of the musician projected onto moving walls that the player must avoid (which tends to focus one’s attention on the logo).

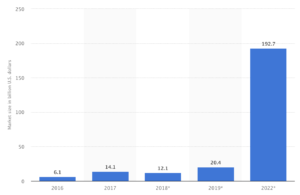

For now these early efforts are mostly experimental. But with the VR industry tipped to grow enormously in the years to 2022, it’s inevitable that we will see new, flexible advertising models in VR to reach consumers who are engaged in ways that were previously impossible.

Advertising within video games is nothing new. One early platformer – Zool – was effectively a game-length advertisement for the lollipop brand Chupa-Chups, while its spiritual successor PepsiMan is still bizarrely fondly remembered (another successor, the Burger King-sponsored Sneak King, less so).

The difference now is that technology and changing video game culture is enabling programmatic buying and selling of in-game ads. For instance, as long as there have been football games, there have been advertising hoardings alongside the pitch. Now, however, technology allows for the buying and selling of those billboards in practically real time, so that brands can be affiliated with a game for as long or short a time as they’d like.

And following a trial last year, Capcom’s Street Fighter V allows players to have brand logos inserted directly onto their character models, in return for an increased amount of in-game currency.

It’s a far cry from the old days when games (particularly in Japan) would negotiate for the rights to use Doritos as in-game items that would heal the main character…

The dream of giant holographic ads is still outside our reach, so we won’t see scenes like those from Blade Runner 2049 or Ghost in the Shell. Given the dystopian nature of those franchises, that’s probably for the best.

Despite that, there have been huge strides made towards attention-grabbing 3D ads, even if they don’t strictly qualify as ‘holograms’. Alasdair Muller, group sales director at The Media Factory, explains: “Most of the technology is not truly hologram technology but is projection or LED-based and merely marketed as such.” Those most common are point-of-sale gimmicks, though it’s likely that will change over the next few years, as Muller explains:

“In today’s crowded digital advertising landscape, consumer attention is a much sought-after currency… So the aim is to capture attention and to hold the viewer’s attention for as long as possible. Holograms certainly grab consumers’ attention and offer the ‘wow’ factor to advertisers.”

So while we don’t (yet!) have Futurama‘s ability to beam advertisements directly into people’s dreams, technology is already enabling brands to reach consumers in ways that would have previously been unthinkable. The future is now.

Already a member? Sign in below

If your company is already a member, register your email address now to be able to access our exclusive member-only content.

If your company would like to become a member, please visit our Front Foot page for more details.

Enter your email address to receive a link to reset your password

Your password needs to be at least seven characters. Mixing upper and lower case, numbers and symbols like ! " ? $ % ^ & ) will make it stronger.

If your company is already a member, register your account now to be able to access our exclusive member-only content.