This question of how advertising-supported consumerism contributes to environmental degradation has been asked by those outside the industry since the 1950s [1]. But it has taken 10 years of Credos’ ‘Big Questions’ for advertising’s think tank to ask the question. This reflects both the increasing focus on advertising’s role in consumption-driven economies and the opportunity for advertising to accelerate the changes in behaviour needed for humankind to live comfortably within the planet’s means.

To date, the relationship between advertising and the planetary crisis facing us all could best be described as ‘uncomfortable’. But as I will argue below, there is evidence that advertising can become a vital tool in building a more sustainable economy.

Advertising has made many contributions to society and the economy through shaping culture, seeding new ideas, encouraging competition and funding information and entertainment. But ultimately, advertising’s existence is down to its ability to power growth. [2]

‘Advertising as we know it was born during the Industrial Revolution, when the capacity to produce goods outstripped the demand for them’ [3], observes historian James B. Twitchell. Following the surge in mass production, companies invested in advertising to boost demand for their products, allowing them to produce and sell ever more of them. This capacity to produce on a previously unimaginable scale, coupled with a tool to sell products and services, led to unprecedented leaps in growth, prosperity, innovation and quality of life. Inadvertently, though inevitably, it also accelerated the burning of fossil fuels, overconsumption of materials, spiralling pollution and loss of biodiversity.

The result is an environmental crisis that is worsening at an ever increasing rate. The UN’s most recent analysis indicates that even if all today’s global pledges are followed through, the temperature rise will be a ‘catastrophic’ 3.1 degrees. This could lead to 250,000 additional annual deaths, 200 million climate refugees by 2050 and a 23% reduction in global GDP by 2100 [4].

In recent years, increased scrutiny has been paid to advertising’s contribution to the crisis. Industry leaders now acknowledge that ‘advertising has undoubtedly played a role in fuelling consumerism’ [5]. Many are beginning to take responsibility for the environmental impact contributed by advertising. Advertised Emissions – the idea (that I helped popularise) that emissions attributable to advertising can be measured – is gaining some traction [6].

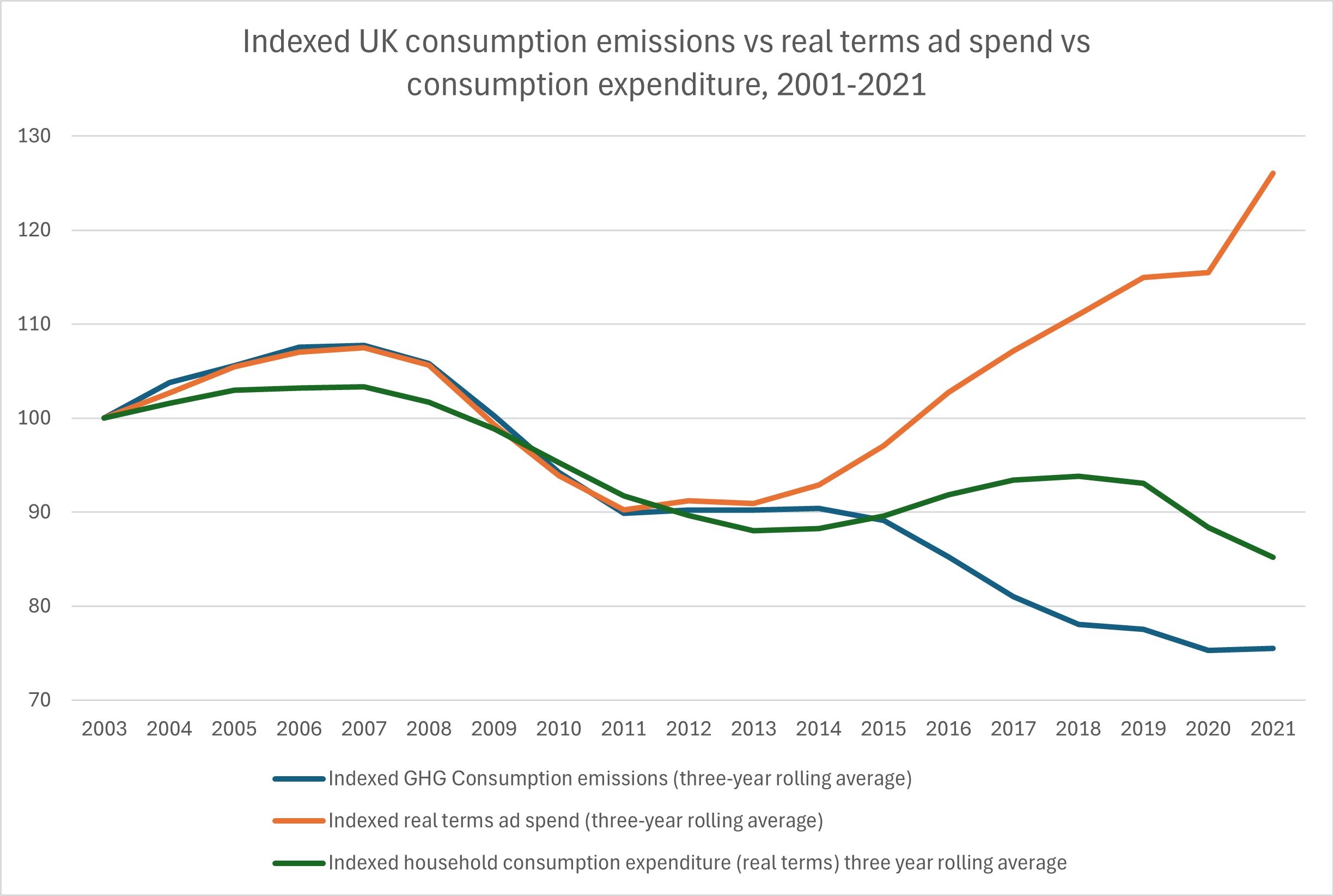

In the UK, there is hope that a pivot in advertising’s role is achievable. As Figure 1 shows, from 2003 to around 2014, advertising spend tracked very closely with the UK’s total ‘consumption’ emissions that include both domestic output and imported goods. Since 2014, however, ad spend has increased dramatically, while indexed consumption emissions have fallen due to government decarbonisation effort particularly in the energy sector.

Figure 1. Indexed UK consumption emissions vs real terms ad spend and consumption expenditure, 2001-2021

But as the CCC has alerted, the UK is slipping behind the transition trajectory necessary to achieve the country’s Net Zero target – with only one third of the required reductions currently covered by credible plans [7]. This has not just planetary implications but economic ones: every year of delay will add disproportionately to the burden in the future.

Which brings us to today, a significant point in history. 2025 is the year global emissions must peak if we are to have any hope of keeping the planet’s temperature rise within 1.5°C [8]. A trendline that has pointed exponentially upwards for over two hundred years [9] must suddenly go rapidly down. If achieved, this will be a pivot point in world history.

So, the question of whether advertising is bad for the planet can also pivot in this moment. To date, through its contribution to the continued growth in consumption and its associated rapid rises in emissions and pollution, most advertising has been bad for the planet. But going forward, as the world pivots towards decarbonisation, advertising can play a vital role in helping urgently reduce all forms of environmental harm.

Because advertising is unique. Through a combination of psychology, creativity and scale, it can shape expectations and desires for how people want to live their lives. That’s why companies today invest a collective $1 trillion in advertising around the world. The industry itself may be relatively small in size, but it is used by companies in every other industry from food to technology to health. And its ability to shape desires, values and behaviours makes it an accelerant of societal change. If we are to achieve the “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” [10] required to avoid the worst planetary outcomes, advertising must not only reduce its carbon footprint through its supply chain but also be a tool in helping other industries reduce theirs.

Most crucially of all, advertising straddles two worlds: corporations and culture. It is therefore uniquely placed to connect a company’s supply-side sustainability targets with the evolving demands of the public. Advertising’s potential impact can be viewed through these two lenses: how it can ignite transformation in supply and how it can accelerate shifts in consumer demand.

How Advertising Can Drive Transformation: The Supply Side

Research suggests that $32 trillion in investment is needed by 2030 alone to stay on track for Net Zero targets [11]. This unprecedented total dwarfs what governments alone can support – up to 70% will need to come from the private sector [12]. And the gap between committed climate finance and the annual level of investment required is currently 85.5% [13]. To unlock this level of private capital, businesses must build confidence that the investment will pay back. This is where advertising can help – as Jeremy Bullmore notes elsewhere in this series, businesses are more likely to invest in new technologies when they know they can market those technologies effectively [14].

Evidence shows that companies who adopt sustainable practices early gain a competitive advantage [15]. Advertising is the key to unlock that advantage, with an observed 11% increase in innovation investment within companies with robust advertising [16]. And over time this can build into a ‘confidence loop’: firms spending more on advertising have a higher likelihood of reinvesting profits into new ventures, expansions, and product development due to the positive market response that advertising provides [17].

The case for corporate investment in sustainability is also strengthened through the reputational (and therefore commercial) impact it can have on brand value. Thanks to ongoing communication of its sustainability initiatives, Apple now derives 3.6% of its total brand value from its perceived sustainability credentials (worth $33.3 billion in 2024 [18]). Protecting this equity becomes a key incentive to maintain high levels of sustainability innovation.

Likewise, Oatly, viewed by UK consumers as the UK’s most sustainable food and drink brand, has combined its sustainability-led mission with distinctive advertising to drive a 4X growth in revenue since 2019. The brand has set out ambitious targets to drive a ‘food system shift’ and ‘lead the charge in a plant-based revolution’ [19].

In enhancing brand reputation, advertising creates the case for further investment in sustainability, thus building a self-fulfilling cycle. This has long-term corporate value: analysis shows the highest ESG rated companies were “more profitable, paid higher dividends and showed higher valuation levels” over 10 years [20].

It has been calculated that 62% of the value of the world’s quoted companies resides in intangible value (20% of which is pure brand) [21]. Sustainability investment is often an intangible asset itself, with no measurable financial payback for many years or even decades. It is vital that companies can capture this long-term commercial potential and turn it into short-term competitive advantage. This is the power of brands and advertising.

Regulation of sustainability messaging

To create the conditions that support this investment, robust and effective regulation of sustainability messages is critical. Without it, brands who ‘walk the walk’ are unable to protect the value of their investments against competitors who just ‘talk the talk’. The rise of greenwashing, where companies exaggerate or fabricate their environmental credentials in advertising, is a significant challenge that undermines the impact of genuine sustainability investment. A 2022 study by the European Commission revealed that over 40% of environmental claims made online were potentially misleading [22], while the number of climate-washing cases filed against firms for making such claims has steadily increased [23]. Without strong oversight, brands that engage in greenwashing risk eroding public trust and disincentivising corporate investment.

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) has intensified its efforts to combat this. Since updating its guidance in 2023, the organisation has banned adverts from major energy companies, aviation, financial institutions and others for exaggerating environmental credentials without sufficient context and transparency.

Beyond cracking down on vague or unsubstantiated claims, of particular focus has been the need for ‘holistic representation of environmental impact’ [24]. Like energy companies promoting their investments in renewables while failing to mention their investment into fossil fuels, brands are now sanctioned for selectively promoting minor investments in sustainability without communicating the negative impacts of their wider operations.

More than just emissions

While the urgency of the climate crisis puts heavy focus on Net Zero and emissions targets, the sustainable investment need is much wider. The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) remind us that sustainability is not just about carbon, but people, water, land, nature and equity [25]. Supply side transformation therefore isn’t limited to renewable energy and low-emission technologies but fair wages, gender equality and decent work. If these items can be elevated within corporate agendas, it can help drive a more complete transformation that addresses not just the environment, but also social well-being.

To support this, advertising can help establish industry-wide sustainability standards like Fair Trade. Evidence shows that in countries such as the UK that have run repeated awareness campaigns for Fair Trade labels, the likelihood of consumers purchasing certified products increases 30-50% [26].

Advertising should help establish similar standards in emerging areas of sustainability such as regenerative agriculture and biodegradable materials, as these can accelerate a more holistic transition across whole product sectors. Building acceptance of these standards puts pressure on brands to adopt them and creates an impetus to strengthen the standards over time.

This front-footed approach is becoming increasingly important as the gap between company climate pledges and real-world delivery is widening. An Accenture report in 2022 said that only a quarter of publicly listed companies currently had validated measurable reduction targets [27], and of those who do, 90% would fail to meet them on current rates of progress [28]. In some cases, short-term financial targets continue to undermine sustainability commitments and the standards set by regulators and coalitions are vital to ensure that business stay on track, while society is not misled into a false sense of reassurance.

How Advertising Can Drive Transformation: The Demand Side

A 2021 report from the UK Climate Change Committee found that 32% of emissions reductions needed by 2035 will depend on shifts in consumer behaviour, from moderating air travel to adopting plant-based diets and choosing longer lasting products [29]. If deployed correctly, advertising can be a key catalyst to these behavioural shifts.

Sustainable product shifts

An obvious way advertising can do this is by encouraging consumers to switch from high- to low-carbon products. By promoting low-carbon alternatives, advertising can do what it’s always done – encourage consumption of certain products – but reduce impact in the process. We can already see this in action in the growing demand for ecotourism, electric vehicles and plant-based proteins – which has now grown to over $10 billion in value by challenging the dominance of traditional meat [30].

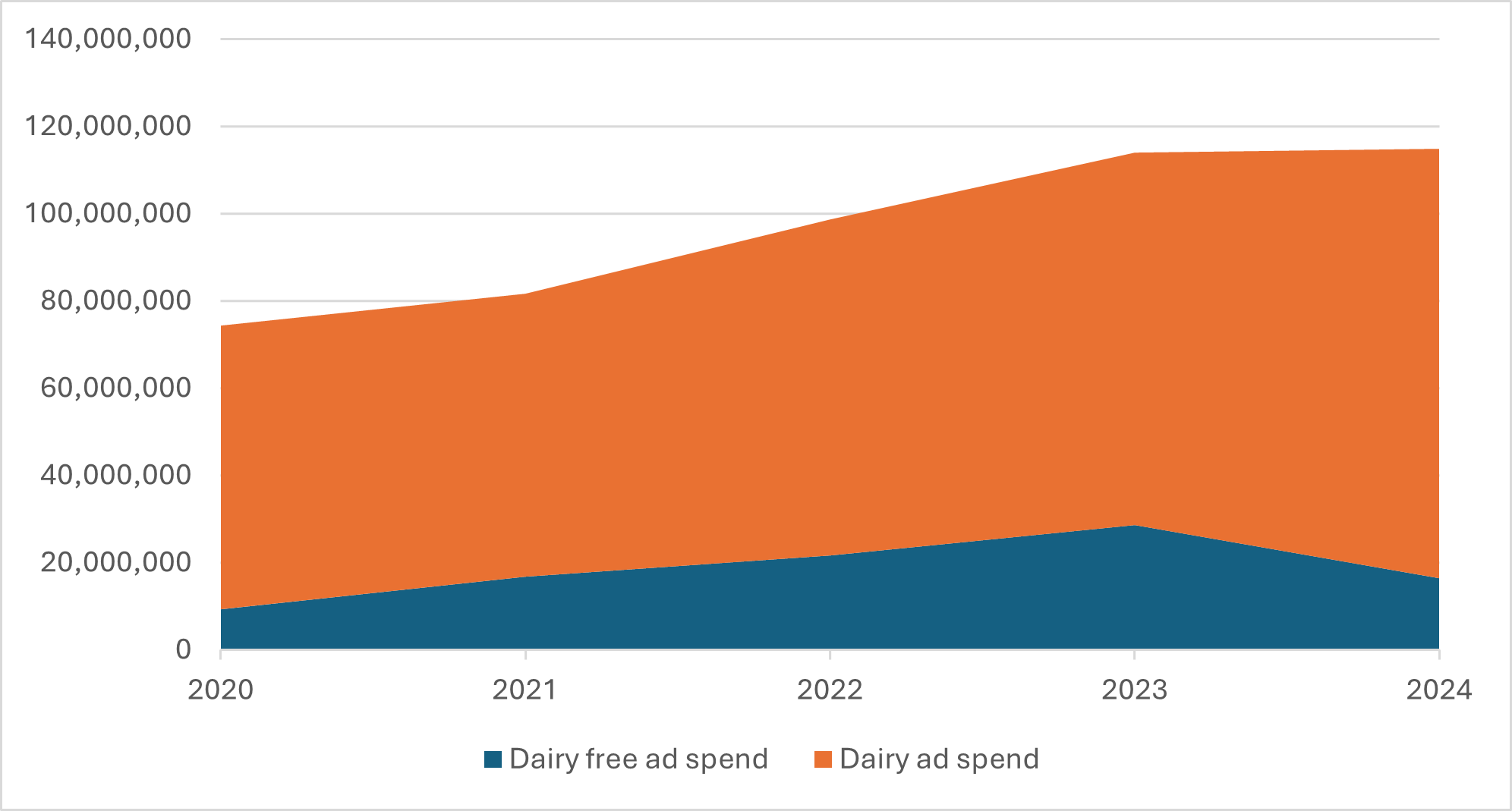

There is growing evidence of the effectiveness of this kind of demand-switching activity. Between 2020 and 2023, spend on dairy-free alternatives tripled, while spend on dairy products grew only 15%. During that time, the dairy-free market growth rate (21.6%)[31] was three times higher than the dairy market (6.7%)[32].

Notably, ad spend on dairy free products fell sharply in 2024, with an accompanied 1.6% drop in unit sales for the sector [33]. The rise from 2020 to 2023 coincided with many high-profile products being brought to market, which commanded large advertising budgets to drum up public awareness. Since the market has stabilised and matured, spend has tailed off, highlighting the importance of advertising in expanding an emerging market.

Figure 2. Dairy ad spend vs Dairy free ad spend, 2020-2024 [34]

Source: Credos analysis of Nielsen Ad Intel data

Behavioural shifts

But simply advertising more products of a different type won’t keep society within sustainability targets. A new electric vehicle for example still has around 50% of the lifetime emissions of a petrol car [35]. Switching the world’s 1.5 billion cars from petrol to electric is not an end in itself and should only be part of the solution.

Advertising must also reinvent those consumption behaviours in a more fundamental way. One technique is to promote responsible or moderated consumption – something that is already common in support of society’s health goals. Thanks partly to advertising programmes such as ‘Drinkaware’ and ‘Dry January’, average weekly alcohol consumption dropped 15% in a decade [36]. Crucially, the value of the industry’s sales continued to grow during this time through premiumisation and innovation. In high-carbon industries that must moderate consumption such as air travel, this is a model to learn from.

There are many other behavioural shifts available, too. The sharing economy, for example, is an economic model where platforms enable providers and users to exchange products and assets, and includes community car clubs, micromobility hire like e-bikes and scooters as well as peer to peer schemes like neighbourhood tool libraries [37].

Advertising has played a significant role recently in driving demand for second hand and refurbished products – 30% of UK consumers reported buying such products in the past year. Well-advertised digital and ecommerce platforms such as Vinted and Backmarket have achieved rapid growth that was kick-started when ‘second hand’ products were rebranded as ‘pre-loved’. Demand accelerated when influencers and cultural partnerships made this the hottest way to shop – examples including 2023’s Campaign Ad Net Zero Award-winning partnership between eBay and ITV’s Love Island [38].

The effectiveness of this creative cocktail of data, technology, psychology and culture demonstrates that advertising can do much more than simply communicate sustainability messages – it can rapidly change behaviour at scale.

Studies report that around 75% of UK consumers expect companies to incorporate environmental messages into advertising [39]. But to effectively drive behaviour change requires ideas rooted in a deep understanding of people’s barriers to adoption, social norms and what it takes for a new behaviour to catch on. These might include supermarkets gently weaning families off high carbon diets through recipe ideas on how to ‘halve the meat’ [40], or energy companies reducing demand spikes through gamified ‘energy saving sessions’ [41].

Beyond promoting the growth of these new consumer models, marketing must evolve to play a key role in the functioning of a sustainable market itself. Currently, most marketing operates as a one-way street – companies produce goods, and advertising matches these products with consumers who use them before discarding them. In a ‘circular economy’, however, marketing will need to become bi-directional, helping to facilitate not just the launch and sale of new goods, but also the re-sale, refurbishment, and recycling of existing products to extend product lifecyles [42].

Currently, only 8.6% of the global economy operates in a circular fashion [43]. But behavioural nudges driven by data of who owns what, who needs what, and where these goods are located can help create a more streamlined circular system. Curry’s ‘Cash for Trash’ campaign was an example of how advertising can help facilitate this system, using a cash trade-in incentive for unwanted tech to facilitate 16 times more cost efficient carbon reductions than offsetting [44]. Brands are beginning to use the tools of targeted data-driven advertising to support the shift from a linear, disposable economy to one where goods are part of a continuous cycle of use and renewal.

Legislation and leadership

For all the potential and positive case studies, however, the products on our shelves today that can be described in some way as ‘sustainable’ make up less than 20% of the total sold [45]. In other words, the majority of products promoted are unsustainable – and some whole sectors, such as aviation, will remain that way for decades.

If the ad industry is unable to make change fast enough, structural changes – led by business, industry bodies or even government regulation – could be demanded to incentivise switching demand from high- to low-carbon products. Talk of advertising bans intensified last year, after both UN Secretary General António Guterres and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Vokler Türk called for one on fossil fuel advertising to combat climate change. While it’s too early to know if bans of this kind will be successful in reducing emissions, restrictions on fossil fuel advertising can already be seen across areas of the EU, including certain UK cities and media owners.

Ultimately, other legislation approaches may prove successful. French legislation passed in 2023 requires brands in the automotive industry to include environmental disclaimers promoting public transport, cycling, or walking. Carbon labelling on advertising, statutory decarbonisation targets, subsidies for green advertising and taxes on the advertising of environmentally harmful products are all powerful measures under discussion in the mould of the tobacco control campaign. Initiatives like these set a precedent for the role regulation can play in not just discouraging the promotion of harmful products, but actively steering consumers towards sustainable choices.

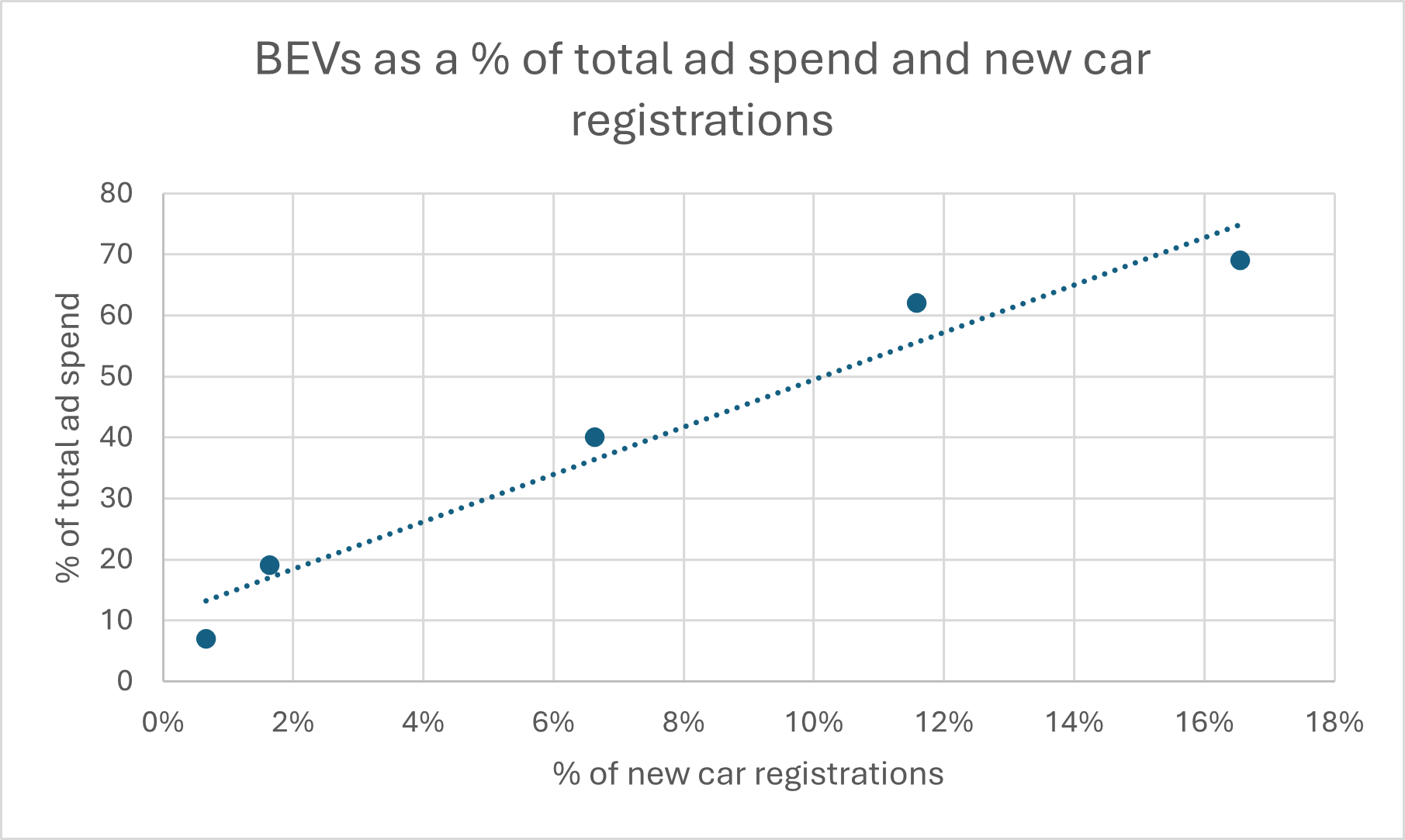

The most effective change happens when advertising and government intervention work in a virtuous cycle. The right communications can create the conditions where tough regulation becomes more publicly palatable. Strong government leadership and regulation makes it easier for organisations to shift their spend, knowing their competitors will be required to do the same. We can see this now in the shift to electric cars in the UK following the 2018 announcement that petrol and diesel vehicles would be phased out: a legal intervention that triggered a transformation in advertising and, with it, demand.

Figure 3 shows the correlation between ad spend on EVs and the percentage of new cars being sold. In 2018, automobile ad spend on electric vehicles (EVs) was just 7%. Fast forward to 2022 and the spend was 69%, while EV’s share of the new care market multiplied from 1% to 17% in that time. Government intervention and a shift in advertising spend had a symbiotic relationship that has begun a shift towards a more sustainable alternative.

Figure 3. Annual EV vehicles % of total ad spend vs annual EV vehicles % of new cars sold

Sources: Nielsen Ad Intel and heycar [46]

Industry groups and individual companies can also drive this change. Several media organisations including Sky and ITV have created schemes to subsidise advertising from innovative sustainable brands [47], while Google has introduced several innovations like publishing emissions data for all flights (though it should be noted that the numbers were revised heavily downwards following discussion with industry partners [48]).

The Advertising Association’s Ad Net Zero initiative has been instrumental in reducing the UK ad industry’s operational carbon footprint, and there is opportunity to extend this influence to where advertising budgets are spent. By creating frameworks that encourage brands to allocate their budgets to sustainable products, both industry bodies and regulators can collaborate to accelerate the decarbonisation of advertising.

Climate impact measurement

Measurement will be key in helping drive these decisions. In 2020, I presented an IPA talk on ‘Ecoeffectiveness’ which described sustainability data as ‘the missing measure’ in the advertising industry’s otherwise robust effectiveness culture [49]. The method evolved to become Advertised Emissions – a UNFCCC endorsed framework that enables organisations to understand the emissions due to the uplift in sales driven attributable to advertising [50]. But there is still much work to be done: exactly how to measure this effectively at scale is not yet clear and has prompted further research from industry bodies such as the IPA and Advertising Association who point out that ‘we must assess the emissions linked to advertising accurately because our industry plays a vital part in a healthy, competitive economy’ [51].

What is clear, though, is that calculating emissions data from advertising campaigns can empower advertisers, media owners and regulators to make informed decisions around how to manage the climate transition. I spoke to one energy company who wanted to calculate the carbon intensity of different advertising campaigns to support the business case for shifting marketing spend from gas boilers to electric heat pumps. In the advertising agency sector, companies have started using the data to support decisions on client new business strategy. Ultimately, this data, and how it is incorporated into the reporting scopes of advertisers, will be significant in making advertising a more effective tool in a sustainable economy.

The big answer

As a form of culture itself, advertising has the power to shape perceptions of what is acceptable and valued within society. 44% of the UK public now see advertising as a driver of social change [52], and the opportunity exists to shift values and prepare society for the difficult choices that the transition will require. To quote climate activist Rafe Pomerance, “behind every political problem, there lies a publicity problem” [53]. Without the necessary societal backdrop, it becomes impossible for politicians, business leaders or people to make the tough decisions required to tackle the environmental crisis.

Is advertising bad for the planet? Or is it a vital part of the solution to the environmental crisis? The answer is both. Advertising is a powerful tool that can be used for either the benefit or detriment of the planet. At an industry level, cooperation is required between government, regulators and trade bodies to put the necessary guardrails in place. We need to make it harder and less lucrative to use advertising in harmful ways, and easier and more appealing to use it in sustainable ones. Whether or not advertising can reimagine itself in this way is yet to be seen.

This is what makes this Big Question unique. Unlike all the others, the answer is yet to be written. Ultimately it will come down to the courage and conviction of the people responsible for commissioning, creating and regulating it. In other words, us. This is not a factual question that can resolved or evidenced one way or another. It is a decision to be taken by everyone who works with advertising. Will we shoulder this responsibility, or not?

Ben Essen is Chief Strategy Officer at Iris, where he has spent 18 years leading strategy for global brands including adidas, Samsung and IKEA. Named Campaign’s #2 Trailblazer in 2021, Ben has been heavily involved in advancing industry thinking on sustainability. Ben supported the creation of the Advertising Association’s Ad Net Zero program and sits on the advisory board for industry sustainability network Purpose Disruptors. He was a lead author of Advertised Emissions, a method for incorporating environmental data into the measurement of advertising performance. He has also won the Admap prize for his thinking on data and creativity and numerous creative strategy and effectiveness awards.

References

[1] https://www.nationalbook.org/books/the-hidden-persuaders/

[2] https://www.warc.com/content/feed/global-advertising-to-top-1-trillion-in-2024-as-big-five-attract-most-spending/en-GB/8558

[3] https://www.jstor.org/stable/40259328

[4] https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/

[5] https://www.wpp.com/sustainability/sustainability-report-2020

[6] https://www.purposedisruptors.org/advertised-emissions

[7] www.theccc.org.uk/2024/07/18/uk-off-track-for-net-zero-say-countrys-climate-advisors/

[8] https://www.ipcc.ch/2022/04/04/ipcc-ar6-wgiii-pressrelease/

[9]https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1352231008011540#:~:text=The%20accelerating%20growth%20rate%20is,since%20the%20pre%2Dindustrial%20era.

[10] https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/

[11] https://about.bnef.com/blog/huge-acceleration-required-for-europe-to-get-on-track-for-net-zero/

[12] https://www.gfanzero.com/press/amount-of-finance-committed-to-achieving-1-5c-now-at-scale-needed-to-deliver-the-transition/

[13] https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2021/

[14] https://adassoc.org.uk/credos/what-is-advertising/

[15]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260219823_How_Green_Marketing_Can_Create_a_Sustainable_Competitive_Advantage_for_a_Business

[16] https://aafroanoke.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/The-Advertising-Coalition-EIA-Final-Report-November-2021.pdf

[17] https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/building-an-engine-for-growth-that-funds-itself

[18] https://www.statista.com/statistics/1487920/brands-sustainability-perception

[19] https://www.oatly.com/oatly-who/sustainability-plan

[20] https://kpmg.com/kpmg-us/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2023/esg-newly-public-companies.pdf

[21] https://www.marketingsociety.com/the-library/how-marketers-should-use-brand-valuation

[22] https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/green-claims_en

[23] https://cssn.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CSSN-Research-Report-2022-1-Climate-Washing-Litigation-Legal-Liability-for-Misleading-Climate-Communications.pdf

[24] https://www.asa.org.uk/topic/Utilities_energy_and_environment.html

[25] https://sdgs.un.org/goals

[26] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-017-3572-9

[27] https://www.msci-institute.com/net-zero-tracker/

[28] https://newsroom.accenture.com/news/2022/nearly-all-companies-will-miss-net-zero-goals-without-at-least-doubling-rate-of-carbon-emissions-reductions-by-2030-accenture-report-finds

[29] https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/behaviour-change-for-achieving-climate-and-environment-goals-environment-and-climate-change-committee-report

[30] https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/meat/meat-substitutes/worldwide#:~:text=Revenue%20in%20the%20Meat%20Substitutes,US$2%2C371m%20in%202024).

[31] ahdb.org.uk

[32] https://store.mintel.com/report/uk-dairy-and-dairy-alternative-drinks-milk-and-cream-market-report

[33] https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/category-reports/a-new-dawn-for-plant-based/697774.article

[34] Dairy category contains: Butter, Cheese – cheddar, Cheese – continental, Cheese- Slices/grated/process, Cheese – Snacks/dips, Cheese – Spreadable, Cheese – UK regional, Dairy – multii product, fresh cream, milk, yogurt – natural/greek, yogurt/fromage frais, yogurt/fromage frais – multi product.

Dairy free category contains: Lifestyle & Dietary – Dairy Alternatives, Lifestyle & Dietary – Milk Alternatives and Margarine & Spreads

[35] https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-how-electric-vehicles-help-to-tackle-climate-change/

[36] https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/drugusealcoholandsmoking/bulletins/opinionsandlifestylesurveyadultdrinkinghabitsingreatbritain/2017

[37] Economic model where platforms enable providers and users to exchange products and assets

[38] https://adnetzero.com/resources/campaign-ad-net-zero-awards-case-study-ebay-love-island-itv/

[39] https://www.techrepublic.com/article/sustainability-trends-uk-2024/

[40] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujk-2uW5oQQ

[41] https://octopus.energy/saving-sessions/

[42] https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview

[43] https://www.circularity-gap.world/2023

[44] https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/campaign-ad-net-zero-awards-winners-2023-computers-electronics-household-appliances-tech/1845039

[45] https://www.retaildive.com/news/sustainable-environmentally-friendly-retail-prodcuts-grow-market-share/646138/

[46] https://heycar.com/uk/news/electric-cars-statistics-and-projections, https://heycar.com/uk/news/car-sales-statistics

[47] https://www.skymedia.ie/sky-zero-footprint-fund/

[48] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-62664981

[49] https://ipa.co.uk/effworks/effworksglobal-2020/ecoeffectiveness-the-missing-measure-in-the-climate-crisis

[50] https://www.purposedisruptors.org/advertised-emissions

[51] https://ipa.co.uk/news/advertised-emissions/

[52] https://adassoc.org.uk/our-work/%20the-social-contribution-of-uk-advertising-2024

[53] https://housmans.com/product/losing-earth-the-decade-we-could-have-stopped-climate-change/