The question of advertising and choice is as old as advertising itself. It has rarely been tackled more definitively than in Keith Boyfield’s essay, The Effects of Advertising on Innovation, Quality and Consumer Choice, commissioned by the Advertising Association in 1992. Boyfield built his thinking on the foundation stone of a 1942 paper by Neil Borden, a Harvard business professor, and he opens with a similar confession:

“The fundamental impact of advertising on the economy has changed little since Professor Borden’s day. Advertising encourages innovation and so encourages choice.”

Boyfield returns again to Borden’s essay to explain how this works:

“…It became evident from case material that many manufacturers have carried out extensive research to find and perfect new products largely because the opportunity for aggressive stimulation of the market for any newly offered product has provided a basis of hope of quickly recovering their development outlay and of getting profit…Without this hope of profit from market stimulation their urge to carry on their search for new products would have been small.”

In short, both Borden and then Boyfield, argue that advertising has a critical supply-side effect. The freedom to advertise or ‘aggressively stimulate’ a market mitigates the risk of innovation investment, and so encourages a greater willingness to take such risks.

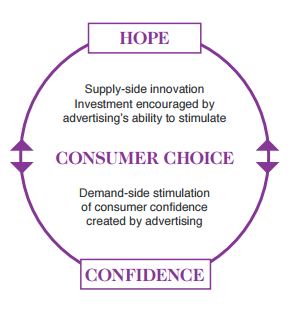

What is being described in both papers is something so ‘commonsensible’ that it takes on the appearance of a universal economic truth across time – from 1942 to 1992 – and place (Borden’s paper studies the US; Boyfield’s the UK). This is a golden rule that can be pictured as a virtuous circle.

The Golden Circle of Innovation

What happens when the circle is broken?

Boyfield’s paper offers vivid evidence of what happens when that virtuous circle is slowed, and the freedom to ‘aggressively stimulate’ is stifled. He uses three powerful case histories as control examples of markets where the corporate ‘hope’ that advertising provides is restricted by regulation: firstly, the optician’s market; then sanitary protection products (sanpro); and finally, and most gloriously, in the command and control economy of pre-glasnost Poland. He shows that, without the hope of advertising, markets stagnate, innovation dries up, and choice becomes stifled.

Looking back now through the lens of the Specsavers Grand Prix IPA Effectiveness paper, who can doubt that choice, service and value have leapt forward since the removal of those restrictions?

Looking back now through the lens of the wonderful ‘Like a Girl’ Cannes winner for Always, who can doubt that teenage girls are better informed since they were allowed to see advertising on the choices available to them?

Looking back now through the lens of the growth of the consumer economy in Poland, who can think it was better for people to wait in queues for sad, half-empty supermarkets to open just to satisfy abstract concepts of market control?

So, if Boyfield proves what can go wrong when the oxygen of advertising is cut – and the last 25 years since his paper was published proves what can happen when oxygen is pumped back into the system – can we now go one step further and prove the benefit more positively; i.e. if we increase advertising, do we get even more choice?

I would argue ‘yes we can’ – if we, again, use our common sense and look around us. Consider your local Starbucks and its orders for ‘skinny, tall decaffs’, ‘caramel Frappuccinos’ and even the odd ‘chai latte’. Apparently, we enjoy five times as much choice in our average supermarkets than we did in 1975, according to the US Food Marketing Institute. That choice extends into every aspect of my life – from the car I choose and the fashion choices I make, and where I make them, to my entertainment. If I want, I can switch and compare nearly anything I choose, to my heart’s or my pocket’s content. We don’t seem to be suffering from a lack of choice; that is for certain. If anything, the suggestion nowadays is that we are deemed to suffer from too much choice.

I ask myself, ‘is it by chance that this super-abundance has grown in line with advertising’s own dynamic growth both in quantity and variety?’. I don’t think so. I would argue that this rise of media choice has actually provided even greater hope for today’s supply-side investor.

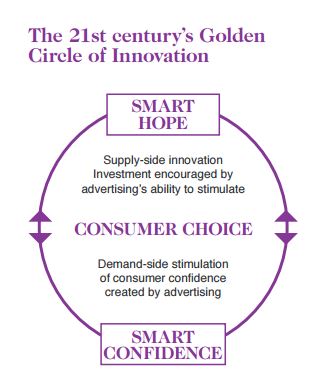

The Golden Circle in the 21st century

Over the last 18 months, I have been working closely with start-ups, helping them to build their business through their brand. I have been able to witness the hope of the Golden Circle up close. The start-up market in the UK is blossoming. Annual rates of registered start-ups have increased from £440k in 2011 to £581k in 2014, with over £600k expected in 2016. Last year, £4 billion in investment (up again from £2 billion the year before) was pumped into those start-ups by venture capitalists, angel investors and crowdsourcing. In short, hope is running high.

A lot of that hope is, of course, not due solely to the rise of advertising opportunity. Money is looking for better returns than it can yield from savings and bonds. Government tax schemes are providing incentives. Local government has created great environments. Recession has created more entrepreneurs. Most of all, from working with start-ups, I have witnessed just how new technology is collapsing the old barriers to entry (such as the need for heavy capital, cumbersome routes to market and difficulties in scaling).

Certainly, we have learnt that it is not the best of times to be an incumbent. Certainly, there has never been a time of greater hope for our new entrepreneurs.

The Golden Circle spins smarter

I would argue that the early 21st century offers even more opportunities to stimulate start-ups than the second half of the 20th century did. Media, like all other areas of life, has exploded with choice. The benefits of that for me as a consumer are obvious, but the benefits of an expanded media choice for start-ups are equally tangible. At its simplest, it allows the Golden Circle to spin more smartly than ever before.

Firstly, the rise and rise of media offers smarter targeting. This allows startups to innovate for a ‘longer tail’ of audiences, surer in the knowledge that they will be able to reach them. In this context, the Golden Circle encourages not just more choice, but a more varied range of choices to connect with a more varied range of audiences. If Henry Ford’s innovation stretched to ‘any colour as long as it was black’, today’s innovation is both literally and metaphorically rainbow-coloured.

Secondly, the rise and rise of last click, low-cost, agile media allows start-ups to grow more smartly, more accountably and efficiently and, most importantly, in more controlled stages. In the early stages, investors can reduce the amount of capital they have to raise to get off the ground, and begin to stimulate demand. Then, in turn, they can invite greater investment at the next stage, on the back of not just MVP (Minimum Viable Product) but also of proven MVM (Minimum Viable Marketing). This means that start-ups can more easily raise larger investments to fuel their marketing funds, and stimulate their demand curve more aggressively. Effectively, modern media choice helps de-risk growth.

Thirdly, the new media world inspires more hope around smarter use of content. The high degree of interconnectedness of digital means that the fame of your business or brand can be more easily ignited and the flames fanned by consumers themselves, acting as your no-cost media. This means wider effects from the same investment. This is all provided ‘of course’ that the content is worthy of being shared and achieving fame in the first place. The good news? This does not necessarily require more money, just more imagination, more bravery and more smarts – all of which, luckily, cost nothing. But the opportunity for start-ups to be as entrepreneurial in their marketing as they are in their business is now definitely there.

In short, the modern abundance of media choice offers opportunities not just for aggressively stimulating demand but for ‘smart aggression’.

The Golden Circle on the consumer side

So, the 21st century’s Golden Circle spins faster and harder for the 21st century entrepreneur. Hope flourishes. But what of the demand side of the equation – what about the consumer? How is the circle working for him or her? How does it give them (more) confidence?

In 1961, George Stigler, Noble Laureate in Economics, argued that advertising is:

“an immensely powerful instrument for the elimination of ignorance – comparable in force to the use of the book, instead of oral discourse, to communicate knowledge”.

I love this idea – that advertising creates consumer literacy in what is, like it or not, a consumer society. And it is this direct benefit of advertising to people versus companies that I would personally stress. For, if the stimulation of markets offers innovators hope for a return on investment, it can also give consumers knowledge with which they can make their equally important decisions on how to invest their equally scarce resources of time and money.

Thinking of advertising in this way, we can see that the rise of media choice in the 21st century has helped the consumer make smarter investment decisions. For, if one thing is clear, it is that the rise of new media offers us all smarter ways of securing knowledge and of being consumer literate. As consumers, more than ever before, we can research before we buy. There is more transparency and company accountability than ever before: more reviews, more peer-to-peer advice and more knowledge sharing. Consumers and investors’ decisions are now better informed.

The 21st century’s Golden Circle of Innovation

In his less heroically broad, but nonetheless impressive, contribution to the advertising and price canon, Charles Young of Ameritest starts from a similar premise: ‘The ability to charge premium prices is the reason why businesses that own brands are generally more profitable than businesses that do not.’ Their higher returns on investment (ROIs) in turn then become the future source of advertising funding.

Young then goes on to tease out the different price expectations created by 11 different Tylenol commercials pretested by his company in the US, demonstrating a variation of 18% across them (from $4.05 to $4.81). Noting as an aside that rational information was less strongly correlated to price expectation than any emotional component (in line with Binet and Field’s own findings), he concludes: ‘By overlooking advertising’s role in supporting premium pricing, and the corresponding contribution it can make in support of higher profit margins, advertisers run the risk of underestimating the return they can make on their advertising investment.’

So, although it is rarely deliberately deployed to do so, we must conclude that advertising can support pricing at an individual brand level.

The downside of choice

The proliferation of choice is good news (in principle at least) for both sides of the circle. But, lest we get too complacent, let us remember one last thing: as I mentioned previously, barriers to entry are falling in nearly every area except one – the consumer’s mind and heart.

From working with start-ups, I have seen that communicating knowledge is too easily confused with this deeper concept of ‘inspiring confidence’. Overlooked perhaps in the excitement of building shiny new tech, there is an almost hidden assumption that a great product will sell itself – a return to the old mantra, ‘Build a better mousetrap and the people will come’. And this sense of self-confidence in the power of the product alone is compounded by the rise of modern media. The mantra can almost be rewritten: ‘Place the information about that mousetrap in better mousetrap media, and surely people will flock!’.

Advertising is seen as an unnecessary cost by some. Indeed, I have talked to venture capitalists who would go as far as banning marketing investments from the balance sheet.

Chief among all is confidence

I have yet to meet a start-up brand – and I have met over 150 in the last year – that does not have five or six competitors attacking the same space. There really is no such thing as clear blue innovation water; there is only the fight to occupy a space in that most valuable real estate of all – the consumers’ hearts and minds. And this requires us to not just overcome that last barrier to entry – consumer inertia – but to do so more attractively, more relevantly, and more engagingly than the other brands.

To achieve this advantage (as the cases used in Boyfield’s essay remind us), our consumers need to learn not just what you are, but what you might mean to them: how it fits into their lives, their sense of self, their image, as much as what it does. In my experience, this continues to be more important in an attention-deficit world. In my business, I advise startups to focus on inspiring consumer confidence, in the most cost-efficient way possible.

21st century cases in building consumer confidence

Let’s take three 21st-century brand examples using the same approach as Boyfield did for his original 20th century cases.

Made.com launched in 2010 as an innovative retailer offering designer furniture direct from the producers. Like First Direct, it discovered early on that it needed to invest in shop window advertising (‘made you look’ became one of its slogans) to compensate for its lack of high street presence and give consumers the confidence to be inspired to buy. And relating to my point earlier of all start-ups having competitors in their field, I read with interest Made.com’s announcement of its new £4 million integrated campaign, which they launched in order ‘to stand out in the sector’. An innovative business model does not distinctiveness make!

Airbnb is a great product: it is disruptive and it creates a genuine new consumer need – it is certainly a better mousetrap. But to maintain its hyper growth, it turned unhesitatingly to advertising in 2015 to give people (beyond early adopters) not only the confidence to use it but to see it as more than just a cheap alternative to hotels: to extend its relevance in people’s imaginations as the new authentic way to explore the world, in a way that allows you to belong anywhere.

I love Deliveroo and Just Eat. They serve an obvious and clear need, which means that we easily notice them; and, if we don’t notice them at first, we quickly spot their delivery drivers weaving their way through the traffic. But I wonder who will win my confidence? Which will become my friend, not just my servant? Which will actually become more meaningful in my life? With new players already crowding in, offering distinctive relevance is the key to succeeding in this new market – not simply awareness and knowledge.

All these start-ups have better products or services. All have smart social marketing and search programmes that efficiently exploit the media environment we now enjoy. However, all three are also recognising that, to aggressively grow and leap ahead of the competition – and to do so in a way that adds magic to their smart marketing – they also need to inspire confidence and create an engagement with their audience beyond the transactional.

We must remember – even in the exciting and heady midst of a Golden Circle spinning ever faster – that this true consumer confidence comes from understanding how to create a true and meaningful ‘why’ in people’s lives, as much as understanding the ‘what’. Real literacy means understanding the poetry of words and what they mean, not just their dictionary definition. Consumer literacy is no different.

In short, innovators need to make things people want and make people want things: to build a brand, not just a business. This is how to create a truly virtuous Golden Circle of Innovation in the 21st century. This was true in 1942. It was true in 1992. And it is as true today as it ever was. Long may that virtuous circle continue.

Want to know a bit more about By Nick Kendall?

Nick is an award-winning brand and advertising specialist with over 30 years’ experience. He joined Bartle Bogle Hegarty in 1986. He has worked on new product launches, such as Häagen-Dazs and Boddingtons, as well as already famous global brands such as Johnnie Walker and Unilever’s cornerstone laundry brand ‘Dirt is Good’.

Nick is an award-winning brand and advertising specialist with over 30 years’ experience. He joined Bartle Bogle Hegarty in 1986. He has worked on new product launches, such as Häagen-Dazs and Boddingtons, as well as already famous global brands such as Johnnie Walker and Unilever’s cornerstone laundry brand ‘Dirt is Good’.

Nick is now a Founding Partner of Bro-Ken and partner in Sir John Hegarty’s incubator, The Garage, which helps start-ups bake in brand ideas from the start. He is also Founding Partner of Electric Glue, an innovative media broker whose aim is to use ideas to ‘glue’ media owner and client ecosystems together. Nick has been convenor of Judges for The IPA Effectiveness awards and author of Advertising Works 10. He also designed and leads the IPA Excellence Diploma, which is described as ‘the MBA of brands’, and remains its Chief Examiner. He is author of What is a 21st Century Brand – a collection of the best essays from ten years of the Diploma. He received the IPA President’s Medal for his services to the industry